The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 7, No. 2,

S1430-4171(02)02550-5, 10.1007/s00897020550a, © 2002 Springer-Verlag New York,

Inc.

The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 7, No. 2,

S1430-4171(02)02550-5, 10.1007/s00897020550a, © 2002 Springer-Verlag New York,

Inc.

The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 7, No. 2,

S1430-4171(02)02550-5, 10.1007/s00897020550a, © 2002 Springer-Verlag New York,

Inc.

The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 7, No. 2,

S1430-4171(02)02550-5, 10.1007/s00897020550a, © 2002 Springer-Verlag New York,

Inc.

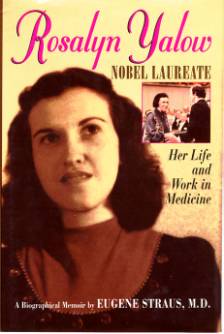

Rosalyn Yalow, Nobel Laureate: Her Life and Work in Medicine. By Eugene Straus, M.D. Plenum Trade: New York, 1998; hardbound, out of print; ISBN 0-306-45796-2; Perseus Press: Cambridge, MA, 2000; paperbound. $16.00. Illustrations. xv + 277 pp. 16.0 ´ 23.5 cm.

George B. Kauffman and Laurie M. Kauffman, California State University, Fresno, georgek@csufresno.edu

On December 10, 1977, in Stockholm’s Konserthus (Concert Hall), Sweden’s King Carl XVI Gustav awarded one half of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Rosalyn Yalow of the Veterans Administration Hospital, Bronx, New York “for the development of radioimmunoassays [RIA] of peptide hormones.” He presented the other half to Roger Guillemin of the Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA and Andrew V. Schally of the Veterans Administration Hospital, New Orleans, LA, both of whom used RIA extensively, “for their discoveries concerning the peptide hormone production of the brain.” Yalow was the second woman to receive this honor (Gerty Therese Cori and her husband Carl Ferdinand Cori had received half of the prize in 1947 “for their discovery of the course of the catalytic conversion of glycogen”), but she was the first American-educated woman to win the prize.

Eugene Straus, M.D., a gastroenterologist, Professor of Medicine and Chief of Digestive Diseases at the State University of New York Health Science Center in Brooklyn, and Yalow’s longtime friend and colleague, begins his “biographical memoir” with her sudden stroke on January 1, 1995, when she was taken to a hospital, where, soiled with blood and unrecognized, she was “dumped” as a charity case onto another hospital. He then contrasts her slow and ultimate recovery from her crippling illness with her earlier, productive years that he chronicles in empathic but objective detail based on his own contact with her and extensive interviews with family and colleagues.

Rosalyn Sussman, sometimes characterized as “Madame Curie of the Bronx,” was born on July 19, 1921 in New York City, as the only daughter and second child of uneducated, lower middle-class Jewish parents. Her father, Simon, of Russian descent, was born on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, and her mother, Clara (née Zipper), had emigrated to the United States from Germany at the age of four. Although neither parent had any education above elementary school, like many other Jews or immigrants, they stressed higher education as a means of upward social mobility for their children.

A willful, headstrong child, Rosalyn became interested in science at Walton High, an all-girl school in the Bronx. In 1941 she graduated magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Hunter College for women (now part of the City University of New York), intending to become a physicist rather than an elementary school teacher as desired by her parents. She received a graduate assistantship in physics (the first woman since 1917), a field then reserved almost exclusively for men, at the University of Illinois, Urbana, where she was the only woman among 400 members of the College of Engineering faculty. In her words, “the draft of young men into the armed forces, even prior to American entry into the World War, had made possible my entrance into graduate school.”

On her first day on campus, September 20, 1941, she met fellow physics graduate student Aaron Yalow, her future husband and an Orthodox Jew who was the son of the chief rabbi of Syracuse, NY. Outshining her male classmates, she earned 21 As in her courses and one A- — in electrodynamics laboratory. The prejudice against women in science at the time was such that the Chairman of the Physics Department told her that she was a good student but “that A- confirms that women do not do well in laboratory work.” Working under the supervision of Maurice Goldhaber, in 1942 she was awarded an M.S. degree in physics and in 1945 a Ph.D. in nuclear physics.

On June 6, 1943, Rosalyn married Aaron Yalow. She believed “that all women scientists should marry, rear children, cook, and clean in order to achieve fulfillment, to be a complete woman.” Yet she is definitely not a feminist. She maintains that “the war gave women like her opportunities, not a feminist movement, and if the opportunities dwindled after the war, she feels that it was because women didn’t want them.” With the help of a longtime maid, her mother, and an understanding and uxorious physicist husband who supported his ambitious and overwhelming partner, she was able to combine career, marriage, and motherhood. She refuses to accept awards restricted to women, which she regards as a sign of reverse discrimination.

Both her children—a son, Benjamin, and a daughter, Elanna, obtained their Ph.D.s and are active in the fields of science fiction and daycare, respectively. In the face of evidence to the contrary, Yalow insists that “her children paid no price for the demands of her scientific career.” Her daughter presents an unflattering portrait of Yalow as a wife, mother, and grandmother: “She just wasn’t physically around…..She didn’t do the kinds of things that parents are supposed to do to make their kids believe that they value what their kids are doing….She was so demeaning to my father, just completely emasculating.” Yet Elanna concludes, “I think she was a pretty wonderful mom.”

After a stint as assistant professor of physics (1946–50) at Hunter College, in 1950 Yalow, who had been introduced to medical physics by her husband and who had been working as a part-time consultant at the Veterans Administration Hospital in the Bronx, became a physicist and assistant chief of the radioisotope service at the hospital. She was joined that same year by Solomon A. Berson, a medical internist who had just completed his residency at the VA Hospital.

In a fortunate, synergistic collaboration and without the aid of even a single research grant the two investigated various medical applications of radioisotopes until Berson died at age 54 of a massive heart attack on April 11, 1972. Although neither would have accomplished alone what they achieved together, Yalow admits that she was luckier than Berson, “because, as a woman and a nonphysician, she needed a male physician to lead the way and protect her.”

By combining techniques from radioisotope tracing and immunology they developed radioimmunoassay (RIA)—the first technique to use radioisotopic techniques to study the primary reaction of antigens with antibodies. This extremely sensitive and simple method for measuring minute concentrations of biological and pharmacological substances in blood and other fluid samples initiated a revolution in theoretical immunology and even all biology itself. In 1959 they first used RIA to study insulin concentrations in the blood of diabetics (Yalow’s husband had diabetes), but their technique soon found hundreds of other applications. Although the commercial ramifications of their new technique were tremendous, according to Yalow, “We never thought of patenting RIA. Of course, others suggested this to us, but patents are about keeping things away from people for the purpose of making money. We wanted others to be able to use RIA.”

Their intensively creative relationship was so close that rumors of an affair between the two circulated, and a previous reviewer of this book even mistakenly referred to Berson as “her second husband.” According to Straus, they “had an intellectual and scientific marriage, never a love affair.” Yalow herself said, “Did Sol and I always get along? Do husbands and wives always get along? No. You have fights and it doesn’t mean anything. It was almost like a marital relationship. The fellows were our children.” At Berson’s funeral the usually emotionally controlled Yalow “wept openly, continuously….her unprecedented display of deep feeling…attracted much attention.” A colleague even declared that Berson had left “two widows.”

Berson’s death was Yalow’s “low point, both professionally and personally.” After his demise Yalow had to show that she was “more than just his technician.” No surviving member of a scientific team had ever received a Nobel Prize. At a dedication ceremony on April 4, 1974, she named her research laboratory, where she had become chief of nuclear medicine in 1970, in honor or her collaborator of 22 years. In 1968 she became research professor at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, where she was appointed distinguished service professor (1974–79), and where in 1986 she became the first Solomon A. Berson Distinguished Professor at large. Yalow was showered with numerous honors, including the prestigious Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award (the first woman to win it), which is often a precursor of the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, the National Medal of Science (the United States’ highest science award), and more than 50 honorary degrees.

In 1991 Yalow retired from the VA Hospital at the mandatory age of 70. Her husband died on August 8, 1992. Because she feels that future generations should provide equal access to scientific careers for people of ability, she states, “I feel that it is now my duty to speak to young women, to encourage them to have careers, and particularly careers in science. I’m very happy to have the opportunity to speak to the girls.”

Straus’ volume is no hagiography. He admits that “Rosalyn has not been universally admired, and that’s an understatement. She has been called arrogant, belligerent, and worse.” His volume, copiously illustrated with 29 figures and each chapter of which is prefaced by a pertinent quotation by Yalow or others, includes lengthy and frank quotes from relatives and colleagues, with many of whom she had strained relationships. His fascinating, compelling, and well-written saga, which reads like a novel, presents a balanced portrait of a “Queen Bee” who “always seemed to command center stage.” An “alpha female, someone who could lead the pack,” she stubbornly refused to compromise her commitment to hard work and scientific integrity.

More than a biography, Straus’ book also deals with gender bias, anti-Semitism, research and patient care in hospitals, the public’s unwarranted fear of radioactivity, microwave ovens, basement radon, and other scientific and societal issues. He details the life and scientific career of an outspoken, aggressive, intensively competitive, critical, and complex woman who has become a role model for female scientists although perhaps not in personal relationships. His book should not only appeal to practicing scientists and historians of science but should also serve as a cautionary tale about the price to be paid by women who wish to pursue a career in science.