The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 11, No.5,

Media Reviews, © 2006 The Chemical Educator

The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 11, No.5,

Media Reviews, © 2006 The Chemical Educator

Media Reviews

The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 11, No.5,

Media Reviews, © 2006 The Chemical Educator

The

Chemical Educator, Vol. 11, No.5,

Media Reviews, © 2006 The Chemical Educator

Media Reviews

Modern Organic Synthesis, An Introduction. By George S. Zweifel and Michael H. Nantz. W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, 2007. 477 pp. £29.99ISBN: 0-7167-7266-3.

There are numerous organic chemistry textbooks available ranging from introductory textbooks for beginning chemistry majors (and nonmajors) to advanced reference materials for trained professionals. The main difference, of course, between the two extremes is the depth of the material and the sophistication with which it is covered. Another major difference for most of these books is that the beginning organic chemistry books have numerous practice problems to work through, while the reference texts have a large array of original literature citations. Modern Organic Synthesis, An Introduction is one of those special books that contains both an abundance of practice problems and plentiful literature citations at the end of every chapter. This text will allow the reader to review material covered in sophomore level organic chemistry classes and bring them to the next level of organic chemistry.

This book has been logically organized into nine chapters. Below is the list of the chapter titles with my summary of the major content for each chapter in parentheses.

· Chapter 1. Synthetic Design (retrosynthetic analysis and selected functional group interconversions)

· Chapter 2. Stereochemical Considerations in Planning Syntheses (conformation analysis and SN2 and E2 reactions)

· Chapter 3. The Concept of Protecting Functional Groups ( protecting amines, alcohols, diols, aldehydes, ketones and carboxylic acids)

· Chapter 4. Functional Group Transformations: Oxidation and Reduction (oxidation of alcohols; allylic oxidations; and chemoselective, regioselective, diastereoselective and enantioselective reductions)

· Chapter 5. Functional Group Transformations: The Chemistry of Carbon-Carbon p–Bonds and Related Reactions (reactions of alkenes and alkynes)

· Chapter 6. Formation of Carbon-Carbon Single Bonds via Enolate Anions (Knoevenagel, Claisen, alkylation of simple enolates, Baldwin’s rules, enamines, aldol reaction and Robinson annulation)

· Chapter 7. Formation of Carbon-Carbon Bonds via Organometallic Reagents (organo-lithium, magnesium, titanium, cerium, copper, chromium, zinc, boron, silicon and palladium catalysts)

· Chapter 8. Formation of Carbon-Carbon p–Bonds (preparation of alkenes and alkenes)

· Chapter 9. Syntheses of Carbocyclic Systems (free radical cyclizations, cation-p cyclizations, pericyclic reactions and ring-closing olefin metathesis)

The book concludes with a two-page epilogue (The Art of Synthesis) that challenges the reader to devise strategic design and synthetic execution of progesterone, (+)-juvenile hormone I, octalactin B, and epothilone D. A full page of abbreviations is located between the epilogue and answers to selected end-of-chapter problems. The authors do explain the abbreviations well in their first occurrences throughout the text, but the abbreviation list would be more accessible inside the front or back cover. A comprehensive index follows the answers section and concludes the book.

Practice Problems: The problems in this text are complex and will challenge both the advanced undergraduate as well as graduate students. The more challenging problems from each chapter have been identified with an asterisk (*) by the authors. Answers to selected end-of-chapter problems are at the end of the book allowing students to check their work and continue their learning process. Answers have not been included for about half of the problems, which could easily allow an instructor to assign some homework problems for grading. Most of the selected answers include original literature citations and about one-fourth of the selected answers contain simply a literature reference. The authors state that this is intended to inform the students on how research is carried out. This will undoubtedly provide the readers with practice in obtaining and understanding references from the literature. Problems in Organic Synthesis (ISBN: 0-7167-7494-1) is a supplement available for this textbook and is due to be released soon. This supplement will include: the end-of-chapter problems from the main text, detailed solution sets, and an extra section of similar problems for advanced students to study.

Literature References: The literature references seem to be accurate, but I did not check them all because there were over 1,000. Many examples are given for original work and some such as those by Kane (1838), Glaser (1869), Schmidt (1880), Reformatsky (1887), Claisen (1890), and Grignard (1900) show the rich history of this field of chemistry. There are also numerous examples of updates, modifications, and reviews. Current literature examples are also present as there are a fair number of references from the current decade. In chapter 9 alone, there was at least one reference from 2000 or more recent issues in Acc. Chem. Res.; J. Amer. Chem. Soc.; J. Org. Chem.; Org. Lett.; Tetrahedron; Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. and Aldrichimica Acta. The references cited for answers to the selected end-of-chapter problems are recent and in well-known journals that should be available at most college and university libraries or via Web access. Those individuals with very little or no literature access to chemistry journals are reminded of the supplemental Problems in Organic Synthesis.

I would suggest Modern Organic Synthesis, An Introduction to anyone who would like to strengthen his or her organic chemistry skills, particularly in multistep synthesis. This book will be very beneficial to advanced undergraduates, graduate students, and those scientists practicing in any field of organic chemistry who would like to review organic reactions and experience organic synthesis. Instructors should strongly consider the implementation of this book for an advanced special topics undergraduate course or as an organic chemistry graduate course.

Robert E. Sammelson

Ball State University, resammelson@bsu.edu

S1430-4171(06)51073-X, 10.1333/s00897061073a

A History of Chemical Warfare. By Kim Coleman; foreword by Thomas D. Inch. Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 6XS, England; 17 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, 2005. http://www.palgrave.com. xxv + 198 pp; 13.7 ´ 21.4 cm.; $85.00, hardbound, ISBN 1-4039-3459-2; $26.95, paperback, ISBN 1-4039-3460-6.

After receiving her Ph.D. from London University, Kim Coleman lectured on modern European history at the University of Essex until 2004. She has acted as a consultant on educational books dealing with nuclear and chemical warfare in the 20th century for the BBC (formerly the British Broadcasting Company). She is currently working on her next book, a comparative history of the World War II Battle of Arnhem in 1944.

According to Coleman,

The purpose of [A history of Chemical Warfare] is to contribute to informed debate by providing an analysis of the development and deployment of chemical weapons from 700 BC to the present day (p xix).

In this post-9/11 era when, hyped by the media, politicians, and other commentators, the specter of possible terrorist attacks is foremost in the minds of most of the population of the civilized world, Coleman’s book is especially significant and timely. In addition to discussing chemical weapons, throughout the book she examines and evaluates the various protocols such as the Hague Declaration (1899), the Geneva Protocol (1929), and the Chemical Weapons Convention (1995) that have tried to bring about either the non-production or destruction of chemical weapons from 1675 to 1997.

Chapter 1, “Historical Precedents?” (10 pp, the shortest chapter), discusses the use of substances such as poison, smoke, pitch and sulfur, and “Greek Fire” (a forerunner of napalm) in ancient times and chemical warfare during World War I, from which certain aspects and their development over later years are described.

Chapter 2, “The First World War” (28 pp), examines this war in great detail because it remains the most important experience of the chemical threat. Chlorine, first used on April 22, 1915 by the Germans near Ypres, Belgium under the direction of later (1918) Nobel chemistry laureate Fritz Haber in an attempt to break the deadlock of trench warfare, and other agents developed by both sides claimed more than 1.3 million casualties, 91,000 of whom died.

It includes a number of technical descriptions of phosgene, Lewisite, mustard gas (dichlorodiethyl sulfide, the “king of gases”), and other chemical agents and considers many wider themes with present-day relevance. One such theme is the nature of the entire development process and the different stimuli that operated at different times. At first, chemical weapons came from chemists anxious to help their countries’ war efforts. Later stimuli included known weaknesses in enemy protective equipment, availability of new weapon delivery systems, and the requirements of changing patterns of warfare. Although military authorities disliked the idea of chemical warfare, their destructive potential compelled them to pay attention to them.

Chapter 3, “The Inter-War Years, 1919–1939” (20 pp), deals with the ways in which public opinion about chemical warfare was aroused after the horrible experience of World War I and, to some extent, how that opinion was exploited. Coleman considers some of this opinion’s effect, including how it stimulated the negotiation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol, one of the most significant pieces of international law prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons. Unfortunately, the protocol applied only to wars between countries, not to civil wars or internal conflicts, and it contained many loopholes and little provision for enforcement.

Coleman also explores chemical warfare national policies and programs during the interwar period and examines the development of new chemical warfare agents in these decades. Among instances of chemical warfare such as the use of poison gas that are discussed are their use by the British against Kurds, Arabs, and Iraqis (1919–1920), by the French and Spanish against the Berbers (1919), by the Italians against the Ethiopians (1935–1936), and by the Japanese against the Chinese (beginning in 1937). [It is not surprising that these indigenous peoples have not forgotten such attacks even though former colonial powers seem to have developed amnesia about these events.—GBK].

Chapter 4, “The Second World War” (21 pp), considers the surprising non-use of chemical weapons and explores the incentives for the different belligerents to use them at different stages of the war and contrasts these with constraints that might have been operating. The incentives to use such weapons were strongest in cases where the homeland was directly threatened and it was to their advantage to reduce enemy mobility. However, the temptation was rejected for reasons varying among different countries but included fear of retaliation against other fronts and civilian populations, personal opposition by political leaders, and absence of trained soldiers and large supplies thought to be necessary for a chemical warfare campaign.

The next two chapters, Chapter 5, “The Soviet Threat, Korea and Vietnam, 1945–1975” (21 pp), and Chapter 6, “The Middle East, Afghanistan, Bosnia and the Gulf” (30 pp, the longest chapter), provide a catalog of cases where the use of chemical weapons has been alleged and describe the rationale governing their use in those instances where the fact of their deployment is beyond reasonable doubt. Before World War II poison gas was used primarily by European countries, whereas after the war chemical weapons were used increasingly by the United States in policing Third World countries such as Korea and Vietnam. Anti-plant agents (Agents Purple, Orange, White, and Blue) used in Vietnam are discussed in detail. The Iran–Iraq War, the first Persian Gulf War, and the present ongoing war in Iraq are considered. Of the last conflict Coleman is not afraid of taking a position, one with which an increasing proportion of the American people now agrees. She states:

In their lust to invade Iraq, the Bush administration and Tony Blair deeply discredited their own nations’ moral standing, credibility and democratic ideals by outrageously misleading their own people and whipping them into mass hysteria to justify a war (p 130).

Chapter 7, “Chemical Terrorism” (19 pp), explores the real and imagined threats from a chemical warfare attack today by assessing to what extent terrorist groups around the world are capable of making and using these weapons. International terrorist attacks for 1996–2000 are classified according to types (firebombing, armed attack, hostage, bombing, and highjacking). Nerve agents are discussed, as are commercial uses of the most important chemical warfare agents (mustard gas, tabun, sarin, soman, and VX). The sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway (“underground”) by members of the Aum Shinrikyo religious sect on March 20, 1995 is thoroughly considered.

Chapter 8, “Controlling Chemical Weapons” (15 pp), focuses on the Chemical Warfare Convention (CWC), the destruction of chemical weapon stockpiles, threats of chemical proliferation by countries (China, Egypt, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Libya, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Syria, the United States, and Yugoslavia) as of 2004. She concludes:

Chemical weapon disarmament has progressed far since the first attempts were made a 100 years previously to outlaw the use of chemical weapons in war. The CWC still holds the best promise for reducing the threat of chemical warfare by building an environment of confidence and security. As well as instruments of verification and inspection, the CWC also possesses resort to aid and assistance in the area of chemical warfare defences in case of attack. In the final analysis, however, the overriding aim of the CWC continues to be the effective ban of all chemical weapons, complemented by the desire to promote the peaceful use of chemicals in industry. Whether such incentives will balance the pressure to acquire such weapons remains to be seen (p 164).

Coleman consulted archives in the UK, Germany, and the United States, and she interviewed a number of persons, including Tom Jackson (U.S. Army), who provided her with eyewitness accounts of napalm attacks in Vietnam during 1970 and 1971. Errors are few and minor, for example, “Yom Kipper” for “Yom Kippur” (War, p 105) and “principle” for “principal” (p 143). Lists of abbreviations and of chemical agents as well as 19 tables reinforce the points of the text. Her meticulously documented volume, which consistently uses British spelling, contains 18 pages of notes (pp 164–182), a bibliography of primary and secondary sources (pp 183–192), and a six-double-column-page index (pp 193–198).

According to Thomas D. Inch, Chairman of the Advisory Committee to the United Kingdom National Authority to the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1995 following the passage of the UK Chemical Weapons Act,

The history of chemical warfare is important so we can learn lessons for the future. Dr. Coleman has provided a well-referenced account of the history. Readers should form their own judgements on the threat chemical weapons pose—whether they really are weapons of mass destruction, their attractiveness to terrorists and the strengths and weaknesses of the Chemical Weapons Convention (p xxv).

I agree with his evaluation of the book, and I am pleased to recommend it to everyone who wants to explore in detail one of the most intriguing but misunderstood areas of modern warfare.

George B. Kauffman

California State University, Fresno, georgek@csufresno.edu

S1430-4171(06)51074-9, 10.1333/s00897061074a

Dear Professor Einstein: Albert Einstein’s Letters to and from Children. Edited by Alice Calaprice; foreword by Evelyn Einstein; with an essay by Robert Schulmann. Prometheus Books: 59 John Glenn Drive, Amherst, NY; Oxford, England, 2002. www.prometheusbooks.com. Illustrations. 232 pp; 13.4 ´ 18.7 cm.; $24.00; hardbound. ISBN 1-59102-015-8.

At the turn of the Millennium Time magazine named Albert Einstein (1879–1955) “Man of the Century,” and he is celebrated worldwide as a cultural icon. Consequently, there is a great demand for readable, factual information about him. Anthologies of Einstein quotes [1] are not only of great value to anyone interested in Einstein but are also of special utility to chemical educators who regularly spice up their lectures with quotations and other items of human interest.

Alice Calaprice, former Senior Editor at Princeton University Press of The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein (1987–1997), in-house Editor for The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, recipient of a National Science Foundation grant for directing PUP's Einstein Translation Project, and recipient of the 1995 Literary Market Place (LMP) Award for Individual Editorial Achievement in Scholarly Publishing, has worked with the Einstein Papers for more than a score of years. In 1996 PUP published her collection of 557 quotations by Einstein, thematically arranged, and 51 quotations about Einstein by others, all with complete reference citations, along with 18 quotations attributed to Einstein, whose sources she could not find. Her handy, pocket-sized anthology of quotations, ranging in length from a single equation (E = mc2) to two paragraphs, also contained an updated family tree that included great-great-grandchildren and a chronology succinctly summarizing Einstein's personal life and career (10 pp) [2].

Four years and 22 foreign language translations later Calaprice updated and greatly expanded her popular, critically acclaimed anthology (from 303 to 450 pages), which included 364 additional quotations (some as long as several pages) and items (preceded with asterisks) [3]. She also made corrections and additions to the original quotations and sources, retranslated awkward passages, and expanded some annotations. She added a new section on music, an appendix, and new information that came to light since the first edition. A number of readers sent her the sources of many of the quotations in the “Attributed to Einstein” section of the first edition, and she inserted the authenticated and documented quotations into the text in the appropriate sections.

In a third and fitting sequel to The Quotable Einstein and The Expanded Quotable Einstein Calaprice uncovers a hitherto neglected side of his personality—his interaction with children and the delight that he took in them. She has collected and edited a selection of more than 60 delightful and charming letters, most never published before, sent to Einstein from children around the world—Japan, South Africa, the Netherlands, Germany, England, and mostly from America, when he lived in Princeton—and his considerate and often witty replies. Her book, with dimensions only slightly larger than its two predecessors, is “dedicated to the children of the world,” and the author will donate a portion of her royalties from the book’s sale to the United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF). According to Einstein’s granddaughter Evelyn Einstein, who lost her grandfather when she was 14 and who wrote the foreword, which contains anecdotes about him (pp 9–14 p),

This collection is a fine representation of the esteem that children had for my grandfather, and of his willingness to respond to some of them even though he was busier than most people. He respected children and liked their curiosity and fresh approach to life and therefore did not want to ignore them. It is clear to me, however, that, unlike most of today’s letters from celebrities, his words are his own. I hope the letters will inspire kids to partake again in the declining art of correspondence so that legacies such as these can be left for future generations (pp 13-14).

However, the book is much more than a collection of letters. Calaprice presents a useful 10-page “Chronology of Einstein’s Life” (pp 23–32) and a short biography titled “I am merely curious” (pp 33–70) that includes almost every aspect of his life, career, and achievements. Then Robert Schulmann, the former Director of Princeton University’s Einstein Papers Collection, discusses “Einstein’s Education” (pp 71–81), which should interest both teachers and parents. He explains from Einstein’s own experiences his educational philosophy and why he condemned the “grill-and-drill” procedures and final examinations that “destroy a pupil’s curiosity and sense of individuality, the most precious gifts that an education can and should nurture and reinforce” (p 81). He also seeks to dispel the myth of Einstein’s poor grades in secondary school (pp 77–78).

“An Einstein Picture Gallery” (pp 83–110) features 26 photographs, many previously unpublished, of him alone and with others, largely children, dating from his age of three to 1953. Here we find him with an Indian headdress (p 93), carrying a puppet of himself (p 94)), sailing on his boat (p 97), wearing fuzzy slippers (p 108 and on the book’s dust jacket—See accompanying illustration). His image, among others, in the archway of the door to New York City’s Riverside Church appears on p 91. He was the only living person, Jew, and scientist so honored. An additional nine illustrations are included in “ I Am Merely Curious.”

Almost half of the book consists of “The Letters” (pp 111–220), which span the years 1928 to 1955, the year of Einstein’s death, and they reveal the intimate human side of perhaps the greatest scientist of all time. All the young letter writers are now middle-aged or old-aged, and some are probably deceased. Although Einstein spent much time contemplating the impersonal abstractions of mathematics and physics, he was very fond of children and thoroughly enjoyed their company. Children wrote to him for letter-writing projects assigned by teachers, out of curiosity, as members of “Einstein clubs” for children interested in the sciences, or because of prodding from a parent.

The dated and meticulously annotated letters and occasional postcards, amusing, touching, and sometimes very precocious, are presented in full except for cases of excerpts from long letters to his younger son Eduard (pp 111–112) and older son Hans Albert (pp 146–147; 177–178), both originally in German. Some of them display the innocence and spelling errors of childhood; others show an undoubting awareness of Einstein’s fame. In many the children want Einstein to know who they are by including many personal facts about themselves. Some are wishes for his 70th birthday (He was born on March 14, 1879; my younger daughter Judith shares his birthday but was born in 1961). Except in a few cases of previously published letters, Calaprice has used only the first names or initials of the children to avoid any possible invasion of privacy.

Some of the questions that the kids asked are perennial ones: “Do scientists pray, and what do they pray for?” (p 127); “Is time the fourth dimension?” “What holds the Sun and planets in place?” “I would appreciate it very much if you could tell me what time is, what the soul is, and what the heavens are?” (p 141); “If nobody is around & a tree falls, would there be a sound, & why?” (pp 144–145). One letter is from a Jewish refugee girl thanking him for helping her family to obtain a visa to emigrate to the United States, a service that he rendered to many families during the 1930s and 1940s (p 176).

Another especially poignant letter (pp 181–183) is from an anguished father whose 11-year-old son died of polio, a not uncommon happening during the summers of those pre-vaccine times:

I have just read your volume The World as I See It [in which you stated]: “Any individual who should survive his physical death is beyond my comprehension.…such notions are for the fears or absurd egoism of feeble souls.” And I inquire in a spirit of desperation is there in your view no comfort, no consolation for what has happened? (p 183).

Einstein replied empathically but did not compromise his beliefs:

A human being is part of the whole world, called by us “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind (p 189).

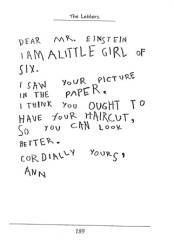

Eight of the letters are accompanied by reproductions of the letters themselves. As an amusing case in point (See the accompanying illustration):

I am a little girl of six. I saw your picture in the paper. I think you ought to have a haircut, so you can look better (p 189).

An “Afterword” (pp 221–223), “Additional Reading” (21 books for the general public from 1931 to 2002; four books for young readers from 1984 to 1997; pp 225–227), and a 3-double-column-page index with page numbers for illustrations in italics (pp 229–232) conclude this enchanting compilation, in which Einstein “has left a legacy matched by few and remains a role model for generations of young people to come” (p 223). It should be welcomed by Einstein aficionados, teachers, parents, and all the young, budding scientists in their lives. Its modest price and handy size make it an ideal gift for such persons.

References

1. Dukas, H.; Hoffmann, B., Eds. Albert Einstein, The Human Side; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1979.

2. Calaprice, A., Ed. The Quotable Einstein; foreword by F. Dyson; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1996. For a review see Kauffman, G. B.; Kauffman, L. M. Am. Scientist 1998, 86, 82–83.

3. Calaprice, A., Ed. The Expanded Quotable Einstein; foreword by F. Dyson; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ; Oxford, England, 2002. For a review see Kauffman, G. B. Chem. Educator 2002, 7, 239–241; DOI 10.1333/s00897020586a.

George B. Kauffman

California State University, Fresno, georgek@csufresno.edu

S1430-4171(06)51075-8, 10.1333/s00897061075a

The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, Third Edition. Lester R. Morss, Norman M. Edelstein, & Jean Fuger, Editors. Joseph J. Katz, Honorary Editor. Springer: P.O. Box 17, 3300 AA Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. http://www.springer.com. 5 volumes, Figures, tables, and indices, clxxv + 3440 pp.; 16.9 ´ 24.6 cm.; hardcover. $1800.00; ISBN 1-4020-3555-1; e-book; ISBN 1-4020-3598-5; http://springer.com/ebooks.

The first edition of this work, then titled The Chemistry of the Actinide Elements [1], which explained and interpreted a relatively new field of chemistry, appeared in 1957, almost half a century ago. After all, the actinide concept—that these elements were members of an actinide (5f) series similar to the lanthanide (4f) series—was first proposed only 13 years earlier by 1951 Nobel chemistry laureate Glenn T. Seaborg (1912–1998), one of the authors of the monograph. The other author was Joseph J. Katz (b. 1912), who guided, motivated, and led the editors and contributors of the third edition, and consequently is listed on the title page as Honorary Editor.

At the time of the publication of the first edition, the chemical properties of thorium (At. No. 90) and uranium (At. No. 92) had been investigated for more than a century and those of actinium (At. No. 89) and protactinium (At. No. 91) for more than half a century, but all the properties of neptunium (At. No. 93) and heavier elements and much of the newer chemistry of uranium had been discovered only since about 1940. In 508 pages the first edition described the chemical properties of the first transuranium elements, neptunium, plutonium (At. No. 94), and americium (At. No. 95), in considerable detail, but the last two actinide elements (Nobelium, At. No. 102, and lawrencium, At. No. 103) had not yet been discovered.

By 1986, the date of the publication of the second edition [2], all of the actinide elements (At. Nos. 90–103) had been synthesized and characterized to some extent. The now two-volume set contained a separate chapter for each of the elements except for the elements beyond einsteinium (At. No. 99), which were combined into one chapter, and it systematically dealt with various aspects of the chemical and electronic properties of the elements, ions, and compounds caused by the filling of the 5f subshell. Although six transactinide elements had been synthesized by 1986, their experimentally determined chemical properties occupied only 1-1/2 pages of text in this edition.

By 1997 Katz, Seaborg, and Lester R. Morss, the editors of the second edition [3], realized that the study of the chemical properties of the actinide elements had progressed to the extent that distinct subdisciplines had emerged. These areas had matured sufficiently so that researchers could make more substantial contributions to predicting and controlling the fate of actinides in the laboratory, technology, and the environment. Scientists in the field now understand and can predict to some extent the chemical bonding and reactivity of actinides in actinide materials, actual environmental matrices, and proposed nuclear waste repositories. In addition to nuclear research groups working on the actinides, similar groups in various countries have conducted systematic and important experimental investigations on the transactinides for several decades. For these reasons the editors began to work on a third edition, titled The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements, which would be more extensive and deeper than the second edition.

The latest edition is edited by Lester R. Morss, Norman M. Edelstein, and Jean Fuger. Morss, a retired scientist from the Argonne National Laboratory, is Program Manager for Heavy Element Chemistry at the Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy, Germantown, Maryland. Having served on the faculty at Rutgers University (1971-1980) and as an actinide chemist at the Argonne National Laboratory (1980-2002), he carried out research on lanthanide and actinide elements, especially the transuranium elements. His publications deal primarily with thermochemistry and structure-bonding relationships among metals, oxides, halides, and coordination compounds.

Edelstein is a Senior Staff Scientist, Emeritus, Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, where he was Head of the Actinide Chemistry Group (1972–2000), until he became temporary Program Manager for Heavy Element Chemistry at the Office of Science, U.S. Department of Energy, Germantown, Maryland. His primary research interests involve the optical and magnetic properties and electronic structure of the actinides and lanthanides; the general, inorganic, and solution chemistry of the actinides; and synchrotron radiation studies of actinides and other environmentally relevant materials. Fuger, Professor Emeritus at the Université de Liège, Liège, Belgium, where he taught courses on radiochemistry, analytical chemistry, and related subjects, was formerly associated with the Inter-University Institute for Nuclear Sciences in Brussels and the University of California, Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, and was Head of the Chemistry Division (1986-1988), Scientific Coordinator (1988-1990), and Deputy Director (1990-1997), retiring from this last position in 1997. His research interests center on the structural and thermodynamic properties and solution chemistry of the lanthanides and actinides and their compounds.

All three editors contributed to Chapters 1 and 15 (along with Joseph J. Katz). Also, Morss contributed to Chapters 2 and 19; Fuger contributed to Chapter 19; and Edelstein contributed to Chapter 20.

The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements is dedicated to Joseph J. Katz, who contributed to the volume, and to the memory of Glenn T. Seaborg, who participated in the planning but unfortunately died before any of the chapters had been written. It follows the plan of the first edition but also includes full consideration of the transactinide elements:

This book is intended to provide a comprehensive and uniform treatment of the chemistry of the actinide elements for both the nuclear technologist and the inorganic and physical chemist (p xvi).

Like Julius Cæsar’s Gaul, this third edition is divided into three parts. The first part follows the format of the first and second editions by starting with chapters (1–14) that describe and interpret the chemical properties of individual elements or groups of elements, including substantially updated treatment of the chemistry of all the actinides and authoritative reviews of the chemical properties of the transactinides. The second part (Chapters 15–26) summarizes and correlates physical and chemical properties generally unique to the actinide elements because of their partially filled shells of 5f electrons, whether present as isolated atoms or ions, metals, compounds, or ions in solution. The third part (Chapters 27–31) deals with specialized topics that involve contemporary fields related to actinide species in the environment, the human body, storage, or wastes. Two separately paginated appendices tabulate important nuclear properties of all actinide and transactinide isotopes.

Each chapter is intended to provide enough background for readers who are not specialists in actinide science, nuclear-science-related areas (nuclear physics, health physics, or nuclear engineering), spectroscopy, or solid-state science (metallurgy or solid-state physics). Collectively, the set provides a balanced and insightful treatment of the current, cutting-edge research on these elements and related topics.

Although The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements is an international venture, most (49) of the 72 contributors, who are all eminent authorities from academic, industrial, and governmental laboratories working in 14 countries are based in the United States. The others hail from France (5), Germany (5), Japan (3), Russia (2), and Belgium, the Czech Republic, India, Israel, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom (one each). Two of the contributors are now deceased (Mark Fred and Harold W. Kirby), and ten are retired. Prominent nuclear scientists such as Katz, Darleane C. Hoffman, and Gregory R. Choppin, winners of the American Chemical Society’s Glenn T. Seaborg Award for Nuclear Chemistry in 1961, 1983, and 1985, respectively, are the rule rather than the exception for contributors. Norbert Trautmann of the Universität Mainz, a coauthor of Chapter 16, will receive the Seaborg Award at the 233rd National Meeting of the ACS, Chicago, IL, March 25-29, 2007.

The meticulously documented volumes, which are cumulatively paginated, are printed on heavy, glossy, acid-free paper and include 723 numbered figures (diagrams and photographs) and schemes and 454 numbered tables (some several pages long) as well as numerous unnumbered reaction schemes, mathematical, chemical, or nuclear equations, and tens of thousands of references, some as recent as 2005. All of the chapters contain numbered sections and subsections, and some contain glossaries, lists of abbreviations, and discussions of future trends. Each of the set’s five volumes contains the following items for the entire set: a table of contents (3 pp), a list of contributors and their affiliations (5 pp), preface (2-1/3 pp), and subject index (33 double-column pages). The final volume also includes a 157-double-column-page author index.

The contents of the work give some idea of its breadth and depth:

Volume 1 (xvii + pp 1-698; Index, I-1-I-33)

· Chapter 1. Introduction (17 pp, 4 Figures, 1 Table, the shortest chapter)

· Chapter 2. Actinium (34 pp, 8 Figures, 4 Tables)

· Chapter 3.Thorium (109 pp, 19 Figures, 17 Tables)

· Chapter 4. Protactinium (92 pp, 19 Figures, 18 Tables)

· Chapter 5. Uranium (445 pp, 75 Figures, 40 Tables)

Volume 2 (xvii + pp 699-1395; Index, I-1-I-33)

· Chapter 6. Neptunium (114 pp, 14 Figures, 14 Tables)

· Chapter 7. Plutonium (452 pp, 126 Figures, 58 Tables, the longest chapter)

· Chapter 8. Americium (131 pp, 17 Figures, 9 Tables)

Volume 3 (xvii + pp 1397-2111; Index, I-1-I-33)

· Chapter 9. Curium (47 pp, 4 Figures, 4 Tables)

· Chapter 10. Berkelium (55 pp, 8 Figures, 5 Tables)

· Chapter 11. Californium (78 pp, 10 Figures, 16 Tables)

· Chapter 12. Einsteinium (44 pp, 13 Figures, 8 Tables)

· Chapter 13. Fermium, Mendelevium, Nobelium, and Lawrencium (31 pp, 1 Figure, 8 Tables)

· Chapter 14. Transactinide Elements and Future Elements (101 pp, 24 Figures, 15 Tables)

· Chapter 15. Summary and Comparison of Properties of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (83 pp, 8 Figures, 12 Tables)

· Chapter 16. Spectra and Electronic Structures of Free Actinide Atoms and Ions (57 pp, 15 Figures, 7 Tables)

· Chapter 17. Theoretical Studies of the Electronic Structure of Compounds of the Actinide Elements (120 pp, 34 Figures, 23 Tables)

· Chapter 18. Optical Spectra and Electronic Structure (99 pp, 31 Figures, 14 Tables)

Volume 4 (xvii + pp 2113-2798; Index, I-1-I-33; the shortest volume)

· Chapter 19. Thermodynamic Properties of Actinide and Actinide Compounds (111 pp, 33 Figures, 39 Tables)

· Chapter 20. Magnetic Properties (82 pp, 19 Figures, 14 Tables)

· Chapter 21. 5f-Electronic Phenomena in the Metallic States (73 pp, 23 Figures, 2 Tables)

· Chapter 22. Actinide Structural Chemistry (144 pp, 41 Figures, 34 Tables)

· Chapter 23. Actinides in Solution: Complexation and Kinetics (97 pp, 25 Figures, 29 Tables)

· Chapter 24. Actinide Separation Science and Technology (17 pp, 28 Figures, 18 Tables)

Volume 5 (xvii + pp 2799-3440; Indexes, I-1-I-33 and I-35-I-157, the longest volume if indexes are included)

· Chapter 25. Organometallic Chemistry: Synthesis and Characterization (112 pp, 40 Figures, 6 Tables)

· Chapter 26. Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalytic Processes Promoted by Organoactinides (102 pp, 35 Figures, 4 Tables)

· Chapter 27. Identification and Speciation of Actinides in the Environment (73 pp, 19 Figures, 8 Tables)

· Chapter 28. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy of the Actinides (113 pp, 7 Figures, 13 Tables)

· Chapter 29. Handling, Storage, and Disposition of Plutonium and Uranium (74 pp, 9 Figures, 9 Tables)

· Chapter 30. Trace Analysis of Actinides in Geological, Environmental, and Biological Matrices (66 pp, 10 Figures, 4 Tables)

· Chapter 31. Actinides in Animals and Man (102 pp, 4 Figures, 1 Table)

· Appendix I. Nuclear Spins and Moments of the Actinides (1 p)

· Appendix II. Nuclear Properties of Actinide and Transactinide Nuclides (33 pp)

The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements is among the more than 150 new chemistry books per year that are made available per year in electronic format in the Springer eBook Collection advertised as “the world’s most comprehensive digitized scientific, technical and medical (STM) book collection,…the first online book collection especially made for the requirements of researchers and scientists.” The collection, which currently consists of more than 12,000 books and increases by more than 300 books annually, is accessible on http://springerlink.com and is intended to increase the rapidity of newly published research. It employs the “portability, searchability, and unparalleled ease of access of PDF and HTML data formats to make access as convenient as possible.” It is designed to provide instantaneous, convenient access to book content wherever and whenever needed, is hyperlinked through easy-to-use browsing and search functions, is searchable on book chapter level, and is integrated with Springer Online Journals. For additional information or to find the local Springer Licensing Manager log onto http://springer.com/ebooks. Also, visit http://reference.springerlink.com for complete details or to sign up for a free 30-day trial.

In the words of the editors of The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements,

[We] hope that this new edition will make a substantive contribution to research in actinide and transactinide science, and that it will be an appropriate source of factual information on these elements for teachers, researchers, and students and for those who have the responsibility for utilizing the actinide elements to serve humankind and to control and mitigate their environmental hazards (p xvii).

In my opinion, the editors have eminently succeeded in attaining their goals, I am pleased to recommend heartily this latest edition of a classic monograph to the audience for which they have intended it as well as to scientists and engineers unfamiliar with the field who want to learn how to deal in their research or technology with these two fascinating families of elements at the very frontier of the periodic table. This most authoritative, comprehensive, balanced, and perceptive compilation of the chemical properties of these elements should remain the definitive work on the subject for many years to come.

References

1. Katz, J. J.; Seaborg, G. T. The Chemistry of the Actinide Elements; Methuen: London; Wiley: New York, 1957; 503 pp.

2. Katz, J. J.; Seaborg, G. T.; Morss, L. R., Eds. The Chemistry of the Actinide Elements, 2nd ed.; 2 Vols.; Chapman & Hall: London/New York, 1986; xii + 1677 pp.

3. Books on related topics by the editors include: Loveland, W.; Morrissey, D. J.; Seaborg, G. T. Modern Nuclear Chemistry; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, 2006. For a review see Kauffman, G. B. Chem. Educator 2006, 11, 140–142; DOI 10.1333/s00897061019a; Morss, L. R.; Fuger, J., Eds. Transuranium Elements: A Half Century; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1992. For a review see Kauffman, G. B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 454–455.

George B. Kauffman

California State University, Fresno, georgek@csufresno.edu

S1430-4171(06)51076-7, 10.1333/s00897061076a